Even with a presidential pardon there are still too many in jail for weed

People who have been convicted under federal law can now apply for certifications that their convictions have been pardoned, via a form made available last week by the Department of Justice. While the pardons were automatic, applying for certifications will help the recipients prove to potential employers, landlords, etc. that their convictions no longer stand.

But not all that many people will be helped.

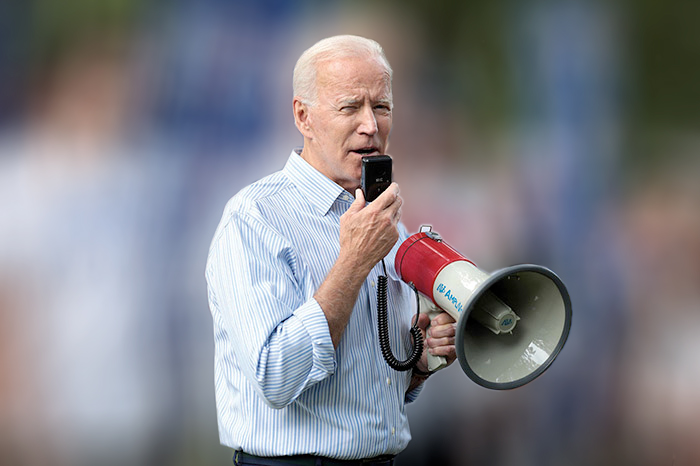

President Joe Biden last October issued a blanket pardon for all people convicted in federal court of simple possession.

Well, not really “all.” Immigrants are excluded, as are members of the military and anyone who was also convicted for selling weed. The president’s announcement drew lots of fanfare at first, but when the caveats became known, the excitement dissipated somewhat.

It turns out the pardons apply to only about 6,500 people. (Like all presidential pardons, these don’t apply to people who have been convicted at the state level. This fact, like the above exceptions, drew a lot of jeers, but that’s just how the law works.)

As is the custom of the Democratic Party, Biden’s move was a half measure and filled with targets for critics on his left to aim at. The exclusion of immigrants from the pardons is particularly irksome for many of those critics.

U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY) tweeted at the time that Biden’s announcement was “truly great news.” But she also said that the president “should treat all people equally and pardon ALL unjust simple possession convictions, not some. If the U.S. is admitting these laws were unjust, then we shouldn’t discriminate pardons [sic] based on citizen status. Let’s get that liberty and justice for ALL.”

The Drug Policy Alliance, which lobbies to liberalize cannabis laws, concurred. The group applauded the pardons but added that “there remains much more to do to provide the relief and justice our communities deserve.”

For starters, the DPA said, Biden should have also pardoned people with convictions for selling weed: If the logic is that pot shouldn’t land people in prison, why pardon only those who bought it, and not those on the other end of the transaction?

Further, the DPA noted, the pardons don’t include expungement of the convictions from criminal records (hence the need for certification).

Biden did win praise for calling on governors to take similar actions in their states, and for calling the Justice Department to “review” how cannabis is categorized in the criminal code: as a Schedule I narcotic, meaning that even now, somebody could be convicted of a major felony by a federal court just for possessing weed.

Members of the military were left out because they are covered by the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and not the code that applies to the rest of the country. There is some confusion over whether Congress would need to be involved in removing pot convictions from the records of active service members.

Even with all the restrictions, most pro-reform observers saw Biden’s move as a step forward, or at least a half-step. But there are still thousands of people languishing in prisons and jails for actions (buying and selling weed) that others are now legally undertaking across the country. And many more are out of jail, but still have criminal records for those offenses.

Before Biden’s pardon announcement, the Last Prisoner Project, which aims to get everybody who is locked up for pot crimes out of the joint, tried to figure out how many are still behind bars. It’s a far more complicated question than it might seem, thanks to the fact that some of the prisoners are also doing time for other crimes, and thanks to the woeful state of government data, and by the sheer number of agencies that run prisons and jails at the federal, state and local levels.

“The best we can do is an educated guess,” the group admitted. That guess: “higher than 40,000.” But how much higher? “We’re not sure. But we are working day-in and day-out to move that needle down to zero.”